Overview

Take advantage of our library of mental health articles.

Written by: Sabina Brown, Psy.D., M.A.

Change at work can bring real feelings of loss and disruption. When colleagues or friends unexpectedly separate from employment while you remain, it’s natural to feel unsettled. Many people experience something akin to survivor guilt, that uneasy mix of gratitude, sadness, and concern for others. This can be part of an experience known as survivor syndrome; a term first used in the late 1990s to describe the experience of those who remain employed after major organizational change.

You might notice worry, fatigue, or uncertainty about the future. Some people feel less motivated or feel disappointed in their leadership; others simply feel unsteady as they adjust. These reactions are normal, and with time and care, they tend to soften.

In the days and weeks after change, it’s common to wonder, “Why them and not me?” or to feel sadness for those who left mixed with relief that you stayed. Even that relief can bring guilt or self-doubt. If you’ve felt any of this, you’re not alone, these are deeply human responses to loss and transition, and part of finding your balance again.

Researcher David Noer, who studies the human impact of organizational change, found that individuals impacted often share similar emotional reactions to large organizational shifts. He emphasizes that realignment is possible, and that individuals can grow through these experiences by acknowledging their feelings, rebuilding stability, and renewing a sense of purpose.

This guide offers ways to regain balance, care for yourself, and move forward through times of change. The strategies below are designed to help you adjust with confidence, renew your energy, and cultivate a sustainable sense of purpose in your work.

Acknowledge What You Feel

Big changes at work can bring up a surprising mix of emotions like relief, guilt, sadness, or even anger. These feelings don’t mean something is wrong with you; they’re natural responses to loss and uncertainty. The first step in healing is simply to notice what you feel.

Try this: Take a few minutes each day to pause and name your emotions without judgment. Writing them down or saying them aloud can help transform what feels overwhelming into something you can hold and understand.

Create Small Anchors of Stability

When your work world shifts suddenly, it can leave you feeling unmoored. Rebuilding a sense of structure through small, steady routines, helps restore a feeling of safety and control. Even small habits can become touchpoints of calm in uncertain times.

Try this: Keep a simple daily rhythm; wake up around the same time, eat nourishing meals, and include one grounding activity like a short walk, a cup of tea, or five minutes of quiet before bed. Rest isn’t indulgent, it’s how we recover our strength.

Stay Connected

After unexpected employment separations or major changes, it’s easy to retreat or isolate. Yet connection is one of the strongest antidotes to stress. Talking with someone you trust can help you feel seen, supported, and less alone in your experience.

Try this: Reach out to a friend, family member, or colleague to share how you’ve been feeling. If others in your household are affected, invite honest conversations about what’s shifting and how you can support one another. If sadness or anxiety persist, consider reaching out to a mental health counselor for extra support.

Reconnect With Meaning

When everything feels uncertain, reconnecting with what truly matters can help you find your footing again. Your values can guide you back toward purpose and balance, even in changing circumstances.

Try this: Write down two or three personal values (for example; integrity, honesty, kindness) and choose one small way to live them at work or in daily life. You don’t need to prove your worth by doing more, showing up with integrity and care is enough.

Moving Forward

Change in the workplace can leave you feeling disoriented, especially when it touches the people and routines that once grounded your day. Within that disruption lies the opportunity to rebuild by caring for yourself in ways that make your work life more sustainable. Each small effort to restore balance, maybe setting clear boundaries, asking for support, or finding steady rhythms, helps you feel more present and capable. Over time, these small choices add up, creating a foundation of stability that allows you to move forward with confidence, purpose, and a renewed sense of connection to your work.

To make an appointment with a counselor at the Faculty and Staff Assistance Program (FSAP) you can submit your online request here (note: UCSF VPN access is required to view the form).

References

Appelbaum, Steven H., Claude Delage, Nadia Labib, and George Gault. “The Survivor Syndrome: Aftermath of Downsizing.” Career Development International 2, no. 6 (1997): 278–286. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620439710178639.

Noer, David M. Healing the Wounds: Overcoming the Trauma of Layoffs and Revitalizing Downsized Organizations. Rev. ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1993.

Niederland, William G. “The Problem of the Survivor: Some Remarks on the Psychic Reactions of Long-Term Concentration Camp Survivors.” Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 9, no. 2 (1961): 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/000306516100900204.

Suicidal thoughts can arise in moments when life feels especially heavy, when stress, pain, or isolation become too much to carry alone. These thoughts don’t always look dramatic or obvious. In the workplace, they may show up quietly through exhaustion, disconnection, or a sense of hopelessness that is hard to name.

Many people who experience suicidal thoughts feel alone or believe they shouldn’t be struggling, especially if they’re used to being the one others rely on. But these thoughts can affect anyone, regardless of role, background, or how things appear on the outside. Recognizing the signs, knowing how to respond, and getting support early can make all the difference.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), suicide rates in the U.S. have increased by approximately 36 percent since 2000, with nearly 50,000 lives lost in 2022 alone. Behind every number is a person, and behind every person is a story that matters.

Recognizing the Signs: When to Seek Support

It can be difficult to determine when it's time to reach out for help. Some key warning signs include:

- Persistent hopelessness or feeling that things will never improve

- Thoughts of being a burden or imagining others would be better off without you

- Expressing frequent thoughts about death or dying

- Giving away personal items or handling final affairs

- Withdrawing from relationships or usual activities

If you or someone you care about is experiencing any of these signs, it is important to seek support immediately. Help is available, and recovery is possible.

Mental Health Challenges Affect Everyone

Mental health struggles do not discriminate by title, role, or performance. Even high-functioning employees, leaders, and deeply caring professionals may experience periods of emotional crisis or suicidal thoughts. These feelings are often internalized or hidden due to stigma, pressure to perform, or fear of being misunderstood.

Seeking support is not a liability. In fact, it is often an act of self-awareness and strength. No one has to navigate this alone.

What You Can Do in the Workplace

Whether you are experiencing distress yourself or want to support someone else, there are meaningful actions you can take.

If You Are Struggling

- Reach out early: You do not need to wait until you're in crisis to seek support. FSAP is here to help whether you're feeling overwhelmed, uncertain, or simply not yourself. Our counselors can also assist with connecting you to a higher level of care if needed.

- Develop a safety plan: A safety plan is a personalized, plan you can create with an FSAP counselor or another licensed mental health provider. It includes warning signs, coping strategies, supportive contacts, and steps for creating a safe environment when thoughts of suicide arise.

- Take meaningful micro-breaks: Short breaks during the workday, such as stepping outside for a few minutes or intentionally disconnecting from screens, can help reduce feelings of overwhelm and provide moments of regulation.

- Adjust workload with support: If needed and when possible, collaborate with your supervisor to adjust expectations, lighten your schedule, or redistribute responsibilities temporarily while you get support.

- Connect to professional care: Therapy and psychiatric services can help address the underlying emotional pain that fuels suicidal thoughts, including depression, trauma, and anxiety.

If You Are Supporting Someone Else

You are not expected to be a therapist. But if you are concerned about a colleague, there are meaningful ways to help:

- Express care: "I've noticed you seem overwhelmed lately. I'm here if you want to talk or need support."

- Refer, don't diagnose: Suggest they reach out to FSAP or another professional support resource. You do not need to assess risk, just help them get to someone who can.

- Know your limits: If someone is expressing suicidal thoughts or you're unsure how serious the situation is, it is appropriate to contact FSAP or a crisis resource to consult. You do not have to manage it alone.

- Don’t keep it a secret: If someone shares something that concerns you, consult with your manager or FSAP to determine next steps. Consultation is available, and your care for that person can be part of connecting them to safety and support.

- Consult FSAP as a leader: If you are a manager, FSAP can also provide leadership consultation to help you support your team in an informed way.

What You Can Say: Simple and Supportive Phrases

Many people freeze in the moment and aren’t sure what to say when they’re worried about someone. Here are a few things that can help:

- "It seems like things have been really heavy for you lately. I'm here if you ever want to talk."

- "You're not alone in this. I'm glad you told me."

- "Would you be open to connecting with FSAP? I can help you reach out if that’s helpful."

- "I'm not sure what the right thing to say is, but I care about you and want to support you."

It is a myth that asking someone about suicide increases their risk. Research shows that asking directly, "Are you thinking about hurting yourself or ending your life?", can actually reduce risk by creating space for honest dialogue. It communicates care, breaks isolation, and opens the door to getting help.

Connection, Meaning, and Strength

Suicidal ideation often arises from deep emotional pain, isolation, and disconnection. Strengthening relationships, meaning, and support systems can offer protection and healing.

Ways to build psychological and emotional resilience include:

- Nurturing personal relationships and expressing emotional needs

- Participating in community or support groups

- Exploring spiritual or faith-based practices, mindfulness, or spending time in nature

- Engaging in creative expression, hobbies, or volunteering

- Seeking therapy to process trauma, grief, or identity-based stress

- Considering medication or psychiatric support if symptoms of depression are severe

Removing access to lethal means and addressing factors such as substance use or burnout can also play a crucial role in prevention.

Take a Moment: A Quick Self-Check

If you're unsure whether to seek support, ask yourself:

- Am I withdrawing from people or responsibilities more than usual?

- Have I lost interest in things that once felt meaningful?

- Do I feel like I can’t talk to anyone about how I’m feeling?

- Have I had thoughts about not waking up or being better off gone?

If you answered yes to any of these, now is a good time to reach out. Support is available, and you do not have to face this alone.

You Are Not Alone

Reaching out for help is not a sign of weakness. It is a courageous act of self-preservation, care, and hope. Many people have moved through dark moments and found their way forward. With support, connection, and resources, healing is always possible.

Support Resources for UCSF Workforce

The Faculty and Staff Assistance Program (FSAP) offers free, confidential support to UCSF faculty, staff, residents, fellows, and postdocs. Services include:

- Short-term mental health counseling

- Leadership consultation for managers

- Officer of the Day (OD) availability for urgent needs

- Referrals for long-term therapy or higher levels of care

Contact FSAP:

- Website: FSAP Website

- After-Hours Crisis Line: 415-476-8279 (available on weekends, holidays, and after operating hour)

The COPE Program

The Cope Program offers mental health referrals for current UCSF staff, faculty, trainees, and their family members. These services are available to all UCSF populations mentioned above, regardless of their personal health insurance carrier or status.

The UCSF Cope Program uses a simple and confidential digital health tool to connect UCSF employees and their families with a wide array of emotional support services. It can be accessed online or by texting @Cope to 1-833-319-1084.

Behavioral Health Benefits Through Insurance

If you would like to access a mental health provider through your UCSF insurance click here for more information.

Emergency and National Support Resources

If you or someone you know is in immediate danger or needs urgent emotional support:

- UCSF Police Department (for on-campus emergencies): 415-476-1414

- San Francisco Police Department (non-emergency line): 415-553-8090

- Call or Text 988: 24/7 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline

- San Francisco Suicide Prevention: 415-781-0500

Additional Organizations to Explore

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP): Education, events, and survivor support

www.afsp.org - National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI): Mental health advocacy and peer support

www.nami.org - Trans Lifeline: Peer support for the trans community

877-565-8860 -

Veterans Crisis Line: Call 988 and press 1

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Preventing suicide: Suicide prevention fact sheet. https://www.cdc.gov/suicide

Unexpected employment separation can be one of life’s most challenging experiences. It affects not just your work but also your sense of stability, identity, and relationships. You may be feeling a mix of emotions (anger, sadness, fear, shock, or uncertainty) and it’s important to know that these feelings are valid and natural. This is a difficult moment, and navigating it takes time.

While this experience is unique to each person, here are some ideas and perspectives that may provide support as you process this transition and begin to move forward at your own pace.

Acknowledging and Understanding Your Emotions

It’s okay to feel what you’re feeling. Emotions like anger, sadness, and grief are natural responses to unexpected loss. This moment may bring up questions about how and why this happened, as well as feelings of uncertainty about the future.

- Give yourself time and space to process. It’s normal to feel a range of emotions, and allowing yourself to acknowledge them, without judgment, can help in making sense of what has happened.

- Express your feelings in ways that feel right to you. Whether it’s talking with someone you trust, writing in a journal, creating art, or engaging in physical activity, finding healthy outlets for your emotions can be helpful.

- Recognize grief as part of the experience. Grief isn’t always linear, and it can take time to move through the different stages. You might find yourself circling back to feelings of denial, anger, or sadness even after reaching moments of acceptance. That’s okay, it’s all part of the process.

Routine & Taking Care of Yourself

In times of uncertainty, prioritizing your well-being can help provide stability and strength. For many people, going to work every day provides a sense of routine and structure. With that now gone, it’s normal to feel a lack of direction or stability. Creating new routines can help fill this gap and provide a foundation to keep you on track during this transition.

- Create a daily routine. Structure can be grounding, and small habits like waking up at a consistent time, eating nourishing meals, or setting aside time for meaningful activities can help you regain a sense of control.

- Focus on your health. Stress can take a toll on both your mind and body, so consider practices that support your physical and emotional well-being. Whether it’s going for a walk, preparing meals you enjoy, meditating, or connecting with spiritual or cultural practices, choose what feels most helpful for you.

Seeking Support

You don’t have to navigate this alone. Staying connected to people who care about you can make a big difference.

- Lean on your support system. Friends, family, and trusted colleagues can offer not just practical advice, but also emotional encouragement. Sharing your experience with others can help lighten the weight you’re carrying. It’s also okay to hold off on sharing until you feel ready.

- Communicate with those affected. If your employment separation is impacting others in your household, open a conversation about how to manage the changes together. Sharing concerns and ideas can help everyone feel more supported and included.

- Accept help when it’s offered. It can be hard to ask for or accept help, but leaning into the support others want to give can be a meaningful way to move forward.

Reframing the Experience

While it may not feel possible right now, this transition could eventually open new doors.

- Reflect on your strengths. Take time to recognize the skills, knowledge, and experience you’ve built over the years. These are valuable assets that you’ll carry into your next chapter.

- Practice kindness toward yourself. It’s easy to fall into self-blame or self-criticism during moments like this, but losing a job is almost always beyond your control. Treat yourself with the same compassion you’d offer a friend going through the same situation.

Exploring Resources

This is a time when reaching out to available resources can provide practical assistance and peace of mind.

- Tap into community services. There may be local or county resources available to help you with financial support, skill-building programs, or job placement services.

- Explore UCSF benefits. If you are eligible, review UCSF benefits that may be available to you both before and after your separation date.

- Seek professional support if needed. Adjusting to unexpected employment separation doesn’t follow a set timeline. If you’re feeling overwhelmed or stuck, a counselor or therapist can offer guidance and help you manage emotions, relationships, and transitions.

Moving Forward at Your Own Pace

This is a challenging time, and it’s okay to take things one step at a time. You don’t have to have all the answers right now, and your path forward will evolve as you gain clarity and confidence.

Remember, this transition doesn’t define your worth or your future. There are brighter days ahead, and when you’re ready, you’ll take the next steps toward them.

UCSF’s Faculty and Staff Assistance Program (FSAP) is here to support employees impacted by employment separation. Our services are available through the end of the calendar month of an employee’s separation date. Schedule a free and confidential appointment by calling (415) 476-8279.

Written by: Sierra Garthwaite, Psy.D.

Procrastination is a common challenge among professionals in high-demand fields, often arising from stress, perfectionism, fear of failure, and emotional avoidance. Rather than a time management issue, researchers increasingly recognize procrastination as a form of emotional regulation gone awry (Eckert et al., 2016). In this model, people delay tasks not because they don’t care, but because completing the task is associated with unpleasant emotions-like anxiety, boredom, or self-doubt.

Researchers have identified common procrastination styles: The Worrier, who hesitates due to fear of failure or self-doubt; the Perfectionist, driven by anxiety and a need to do things flawlessly; the Overdoer, overwhelmed by too many competing priorities; the Crisis Maker, who thrives under last-minute pressure; and the Dreamer, who believes goals can be achieved effortlessly without focused effort (Ai, 2025).

When procrastination becomes chronic, it can impact workplace productivity, personal satisfaction, and mental health. Symptoms may include racing thoughts, guilt, sleep disturbances, or avoidance behaviors such as scrolling, snacking, or rumination.

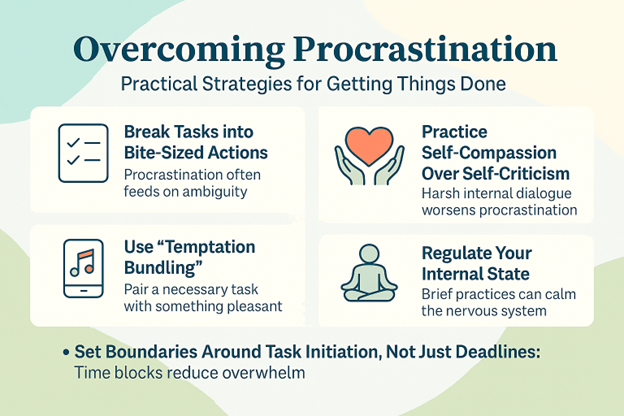

Fortunately, several strategies can help interrupt this cycle:

- Break Tasks into Bite-Sized Actions: Procrastination often feeds on ambiguity. Make a specific plan for when and how you will take action ("If it is 9 a.m., I will open the document") to anchor micro-goals.

- Practice Self-Compassion Over Self-Criticism: Harsh internal dialogue like “I am lazy” or “I always mess this up” can actually make procrastination worse. In contrast, using supportive internal dialogue; for example, saying to yourself, “I am doing the best I can right now” or “It is okay to make mistakes; I can still move forward” can be helpful in reducing the avoidance of tasks. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce procrastination showed that cognitive behavioral therapy reduced procrastination more than other approaches (Eerde & Klingsieck, 2018).

- Use Temptation Bundling: Pairing a necessary task with something pleasant (e.g., listening to music while answering emails) has been emphasized as a method to improve task engagement. James Clear (2018) author of Atomic Habits shares in a website article practical tips on how to create temptation bundles.

- Focus on Managing Your Emotions, Not Just Your Schedule: Strategies like mindfulness meditation, physical activity, or short breathing exercises can calm the nervous system, reducing the emotional resistance to beginning tasks. Results of studies have shown that practicing emotion regulation skills which help individuals navigate aversive emotions reduces procrastination (Eckert et al., 2016).

- Set Boundaries Around Task Initiation, Not Just Deadlines: Establishing consistent boundaries and implementing structured time blocks can foster sustained engagement with tasks while easing overwhelm. Complementary practices such as maintaining regular sleep and exercise routines, nurturing relationships, and enjoying hobbies have been connected to lower risk of burnout (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019).

By addressing the emotional roots of procrastination and implementing manageable, research-backed strategies, we can begin to unstick ourselves and move forward with intention and greater clarity. At UCSF, resources like the Faculty & Staff Assistance Program (FSAP) can provide brief counseling to support professionals struggling with procrastination. Additionally, self-compassion classes and mindfulness-based stress reduction programs can serve as helpful resources.

Citations:

Marcus Eckert, David D Ebert, Dirk Lehr, Bernhard Sieland, Matthias Berking. Overcome procrastination: Enhancing emotion regulation skills reduce procrastination. Learning and Individual Differences, Volume 52, 2016, 10-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.10.001

Ai, K. (2025). Task-specific visualization meditation can overcome procrastination. Arts, Culture and Language, 1(3). https://doi.org/10.61173/11aarf52

Wendelien van Eerde, Katrin B. Klingsieck. Overcoming procrastination? A meta-analysis of intervention studies. Educational Research Review, Volume 25, 2018, Pages 73-85, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.09.002

Clear, James, author. (2018). Atomic habits: tiny changes, remarkable results: an easy & proven way to build good habits & break bad ones. New York, New York: Avery, an imprint of Penguin Random House. Article link: https://jamesclear.com/temptation-bundling

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). Taking action against clinician burnout: A systems approach to professional well-being. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25521

Further Reading:

- Neff, K. D. & Germer, C. K (2018). The Mindful Self-Compassion workbook: A proven way to accept yourself, find inner strength, and thrive. New York: Guilford Press.

- Fishbach, Ayelet (2022). Get it Done: Surprising Lessons from the Science of Motivation. UK: Pan Macmillan.

Written by: Sierra Garthwaite, Psy.D.

Feeling stuck or uncertain is a common experience, particularly in high-stress professional environments such as healthcare, academia, and leadership roles. Decision paralysis often arises when individuals face ambiguous outcomes, emotionally charged choices, or competing values.

Prolonged indecision can lead to emotional fatigue, decreased productivity, and disengagement from meaningful goals. Individuals who struggle to disengage from unattainable goals or delay decisions may report higher stress levels and diminished well-being. This tendency toward overthinking or avoidance is not due to laziness or disinterest. It is often a protective response to uncertainty or fear of making the "wrong" choice.

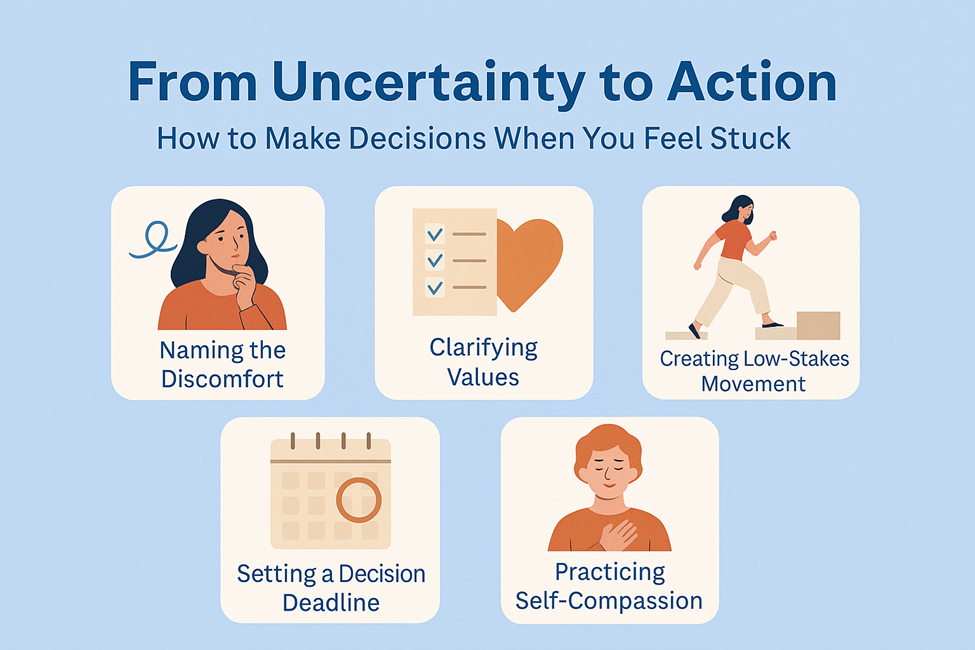

Fortunately, research also highlights practical tools for transforming uncertainty into action. Common strategies for moving from uncertainty to action include:

- Naming the Discomfort: Identify whether the stuckness is due to fear of failure, people-pleasing, anxiety related to perfectionism, or internal conflict between competing values. Morie et al. (2022) proposed that recognizing and identifying an individual's emotions can be a helpful initial step in starting the process of emotional regulation and taking effective action.

- Clarifying Values: Ask, “What’s most important to me in this situation?” The intrinsic theory of motivation suggests that motivation which stems from personal values and genuine interest tends to be more enduring, as it’s fueled internally rather than by external incentives (Bandhu et al., 2024).

- Creating Low-Stakes Movement: Rather than waiting for perfect certainty, try committing to a small action such as an email, a conversation, or a 10-minute planning session. Action-based “scaffolds” have been suggested as a framework to increase motivation through strategies such as frustration control (Belland et al., 2013). Small manageable steps can also increase chances of collecting more information to help inform a decision (Enachescu et al., 2021).

- Setting a Decision Deadline: When appropriate, set a gentle deadline and remind yourself: not all decisions require 100% certainty.

- Practicing Self-Compassion: Rather than judging yourself for indecision, validate the difficulty and recognize the courage it takes to pause and reflect. Kristin Neff (2011) found that higher levels of self-compassion have been related to greater life satisfaction, learning goals, depression, anxiety, and less fear of failure.

The Faculty & Staff Assistance Program (FSAP) offers tools and counseling support for those navigating complex life and career decisions. Ultimately, moving from uncertainty to action doesn’t mean eliminating fear. It means learning to act in the presence of it. Through values alignment, tolerating uncertainty, and self-compassion individuals can begin to move forward with clarity and confidence.

Citations

Morie, K. P., Crowley, M. J., Mayes, L. C., & Potenza, M. N. (2022). The process of emotion identification: Considerations for psychiatric disorders. Journal of psychiatric research, 148, 264–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.01.053

Din Bandhu, M. Murali Mohan, Noel Anurag Prashanth Nittala, Pravin Jadhav, Alok Bhadauria, Kuldeep K. Saxena. (2024). Theories of motivation: A comprehensive analysis of human behavior drivers. Acta Psychologica, Volume 244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104177

Belland, B. R., Kim, C., & Hannafin, M. J. (2013). A Framework for Designing Scaffolds That Improve Motivation and Cognition. Educational psychologist, 48(4), 243–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2013.838920

Enachescu, V., Schrater, P., Schaal, S., & Christopoulos, V. (2021). Action planning and control under uncertainty emerge through a desirability-driven competition between parallel encoding motor plans. PLoS computational biology, 17(10), e1009429. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009429

Neff, K. D. (2011). Self-compassion, self-esteem, and well-being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(1), 1–12. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00330.x

Further Reading:

Heath, Chip, & Dan Heath. (2013). Decisive: How to Make Better Choices in Life and Work. Crown Business.

Written by Romy-Michelle Unger, PsyD.

Emotional regulation is the process of managing our feelings, and it is an important part of mental health (Gross, 1998; MacLeod & Conway, 2005; Hu et. al., 2014). It describes taking action to shift our emotional state to one that is more helpful or preferable. Emotional regulation often comes after the experience of becoming emotionally dysregulated, or feeling an inability to soothe emotions such as anxiety, sadness, or anger, and control how we act on them. Emotional dysregulation can mean that our nervous systems have entered into a fight, flight, or freeze response as a response to a perceived threat, even if there’s no obvious danger in front of us. Essentially, dysregulation takes us out of our baseline and “window of tolerance,” which describes the range of intensity we can tolerate before becoming overwhelmed by stress.

Emotional dysregulation often describes an up-regulation of our emotional state, or an increase of emotional intensity when faced with something we experience as threatening. Some examples of emotional dysregulation include mood swings, irritability, impulsivity, decreased tolerance for frustration, and a tendency to lose one’s temper. One way to notice if we’ve become excessively emotionally dysregulated is if we begin to engage in aggressive behavior, outbursts, crying more than usual, and repeated interpersonal conflicts.

Once we’ve found ourselves in an emotionally dysregulated state — perhaps while caught in a particularly long line at the DMV, or after a break-up, or perhaps after a challenging patient interaction at work — we often engage in emotional regulation strategies to cope, which can range from healthy to unhealthy. Unhealthy strategies include increased substance use, self-harm, doom-scrolling, and binge eating. Healthy strategies, on the other hand, can look like meditation, mindfulness, or deep breathing to calm the nervous system, journaling, exercise or intentional movement, or processing with a therapist or mental health professional.

The next time you notice yourself emotionally dysregulated (which is a huge step; it means you’re increasing self-awareness of your emotional state), take a moment and try to slow down. Take a few deep breaths. Notice the signs of dysregulation as they show up for you. Whether they’re the thoughts that are running through your mind, or the physical sensations, or even perhaps noticing the impact in your relationships — jot them down so you can build a language for yourself to notice your emotional states. Practice taking breaks and allowing yourself to cool off. If you’re noticing yourself getting heated, consider excusing yourself for the bathroom and splashing cold water on your face, or heading to the kitchen and placing an ice cube on your neck (Neacsiu, Bohus & Linehan, 2014). This can help literally and figuratively bring the temperature down.

Citations

Neacsiu, A. D., Bohus, M., & Linehan, M. M. (2014). Dialectical behavior therapy: An intervention for emotion dysregulation. Handbook of emotion regulation, 2, 491-507.

Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of general psychology, 2(3), 271-299.

Hu, T., Zhang, D., Wang, J., Mistry, R., Ran, G., & Wang, X. (2014). Relation between emotion regulation and mental health: A meta-analysis review. Psychological reports, 114(2), 341-362.

MacLeod, A. K., & Conway, C. (2005). Well‐being and the anticipation of future positive experiences: The role of income, social networks, and planning ability. Cognition & emotion, 19(3), 357-374.

Kraiss, J. T., Ten Klooster, P. M., Moskowitz, J. T., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2020). The relationship between emotion regulation and well-being in patients with mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Comprehensive psychiatry, 102, 152189.

Written by: Romy-Michelle Unger, PsyD.

The grieving process after losing a loved one — be it a family member, partner, friend or colleague — is often met with sympathy, understanding, and grace. However, losing a pet can evoke just as deep a grief response as losing a human companion. While the death of a pet can be incredibly impactful on a person’s mental health, the culture around us doesn’t hold such a loss in the same regard, which can contribute to an experience known as disenfranchised grief, or grief that is believed to be illegitimate (Park, R., Royal, K., & Gruen, M., 2023). This can make the grieving process even more challenging for the bereaved, as they can be encouraged by family and friends to move on quickly and replace their pet before they are ready.

It’s important to acknowledge the role that our pets play in our lives. We form attachment bonds to our pets in ways that resemble the attachment bonds we have with relatives and chosen family (Sable, 1995). Pets are often a source of unconditional love that helps their humans navigate difficulties and losses, particularly when human contact was limited during the pandemic (Behler, Green, & Joy-Gaba, 2020). They are dependent on us as their caretakers in ways that help us keep a routine and stay motivated to keep going, even during the most isolating and challenging times.

Sometimes, because of the lack of social approval and support, it’s hard for us to acknowledge that losing a pet impacts us deeply. However, if you are currently experiencing grief from such a loss, it’s important that you give yourself the same grace that you would to anyone who is grieving the loss of a loved one. Feel your feelings as they arise, and give yourself the space to process the loss of your companion.

It is, of course, important to acknowledge that grief has its own timeline and may get activated outside of our conscious control. That said, there are rituals we can use to intentionally carve out space for ourselves to feel challenging emotions within an emotional container. For example, sometimes it can be helpful to set out a candle with a photo of your pet in an area of your home that feels private or special to you (or your pet). After lighting the candle, recall some special moments with your pet, particularly ones that bring up joy, while acknowledging the feelings of loss. Allow yourself to feel the spectrum of elation and grief as the emotions rise and fall. When you feel like you’ve reached capacity, or expressed the emotions you’ve wished to feel, you can blow out the candle. Lighting the candle can act as a symbol of containment for your grief, so you have agency to move in and out of your grieving process. If you feel comfortable, you can invite others to sit with you, and ask them to share their stories as well.

References

Behler, A. M. C., Green, J. D., & Joy-Gaba, J. (2020). “We Lost a Member of the Family”: Predictors of the Grief Experience Surrounding the Loss of a Pet. Human-Animal Interaction Bulletin, (2022).

Packman, W., Carmack, B. J., Katz, R., Carlos, F., Field, N. P., & Landers, C. (2014). Online survey as empathic bridging for the disenfranchised grief of pet loss. OMEGA: Journal of Death and Dying, 69, 333–356. doi:10.2190/OM.69.4.a.

Park, R. M., Royal, K. D., & Gruen, M. E. (2023). A literature review: Pet bereavement and coping mechanisms. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 26(3), 285-299.

Written by: Romy-Michelle Unger, PsyD.

Across cultures, civilizations, and epochs, humans have ritualized their grief via elaborate and time-consuming ceremonies in which whole communities will, for a time, shift their behavior, daily habits, food choices, and even their clothing. The utility of such a practice is that it creates a temporary “container” for the grief — a limited period of time during which daily, regular life has been suspended so that the bereaved can properly mourn and acknowledge that their lives have been forever changed by the loss of their loved one. Another important feature of this is that the community holds the loss with the bereaved, often involving themselves in the ceremony and aftercare providing for those most impacted by grief.

Regardless how these practices and ceremonies have looked or expressed themselves across cultures, they serve a similar function: to create space for the bereaved to process their loss, feel supported by their community, and transition into a new reality without their loved ones’ physical presence. In contrast, our modern, industrialized culture holds very little space for grief; outside of a funeral, memorial service, or obituary, very little communal space is made for individuals to process and feel supported in their bereavement. In fact, our culture largely incentivizes folks to quickly return back to “normal,” leading people to feel pressured to return to work as soon as possible so as not to compromise productivity.

What this can mean for many people is that, after an impactful loss, they may not have community-wide support to assist them in taking time off, pausing their daily activities, and deepening into their bereavement. Of course, many people continue to stay connected to cultural and religious practices that assist the bereaved, and it’s important to lean on such supports during times of loss. For others, however, it becomes even more important to give oneself the permission to take time off, find practices that can both contain and deepen the emotional experience, and remain connected to support systems of various kinds.

Death and dying can stir up deep religious, spiritual, or existential reflections. Whether someone draws meaning from a particular tradition, a secular worldview, or something in between, finding ways to ritualize grief can offer a powerful way to process and contain it.

Part 2 will cover how to ritualize grief.

Written by: Romy-Michelle Unger, PsyD.

A ritual is defined as a pattern of actions performed according to a prescribed order. Rituals are often parts of ceremonies, which tend to be more formal observances of collectively important events or occasions, but can also be performed in a secular, private capacity. Studies have shown that rituals help enhance our sense of control and help reduce anxiety (Brooks et al., 2016; Dygalatas, Maňo, & Pinto, 2021).

This is important because death and grief are experiences that lie largely outside of our conscious control. In a culture that is so focused on individual agency, grief can feel destabilizing as it is one of the human experiences that forces us to confront the limits of the control we have over our lives. Additionally, it’s an emotional experience that has traditionally been held by the community rather than the individual, whether that’s the extended family, religious community, or local network.

In order to regain a sense of agency in our lives, it’s important to think of ways that individuals can experience their grief within a container, or vessel. While historically, religious or cultural ceremonies stood as the container, we can explore ways to ritualize our grief in our own personal ceremonies as well. Setting up a small (or elaborate) altar can serve as a physical place to "put" our feelings, as well as offer us opportunities to honor the loved one we’ve lost in the privacy of our home.

Building an emotional container for our feelings also requires setting up a beginning and end point. This can look like lighting a candle to mark the beginning of the ritual, or lighting incense that shifts the sensory experience in the space. Additionally, it’s important to have a symbolic representation of the person we lost, such as a photo of them or a treasured keepsake that reminds us of them. After we’ve marked the beginning of the ritual, we can allow ourselves to relax into the emotional experience. Hold the keepsake or photo in your sight or even physically in your hands and invite the feelings to wash over you. If you feel called to speak something into the space, do so. This is a container for your feelings, however complicated and paradoxical they may be. It’s an opportunity to speak to sadness, anger, denial and disbelief.

After some time, you may feel "cooked," so to speak — like you’ve expressed what you needed to express and that it’s time to transition. Gently blow out the candle or the incense to signify the end of the ritual. You have now symbolically marked a transition away from the grieving experience, with the understanding that you can come back at any time.

References

Brooks, A.W., Schroeder, J., Risen, J.L., Gino, F., Galinsky, A.D., Norton, M.I., & Schweitzer, M.E. (2016). Don’t stop believing: Rituals improve performance by decreasing anxiety. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 137, 71-85.

Xygalatas, D., Maňo, P., & Pinto, G.B. (2021). Ritualization increases the perceived efficacy of instrumental actions. Cognition, 215, 104823.

Losing a colleague can stir up a wide range of emotions, grief, confusion, guilt or even numbness, each shaped by the nature of our relationship with the person and the context of the loss. Grief is a uniquely human experience that moves in unpredictable waves, rarely following a straight line or fixed timeline. When the person we've lost is a coworker, the emotions may be complicated by questions about how much grief is "appropriate" in a professional environment.

These internal questions are often shaped by the broader culture we live in. Grief is not only personal, it is also sociocultural. Different cultures create different structures for mourning. For example, in Iranian culture, it’s common for colleagues of the deceased to attend the funeral, pay respects to the family, and participate in collective rituals of grief and remembrance. These communal practices provide a clear container for emotional expression and shared healing (Shoraka et al., 2022). In contrast, the dominant culture in the U.S. tends to view grief as private, often placing the burden on the individual to navigate loss independently, especially when the loss occurs within a professional setting.

This can create tension for employees grieving the death of a colleague, someone they may have spent countless hours with, collaborated closely with, or simply shared everyday moments beside. It can also feel disorienting to grieve someone with whom the relationship was meaningful but existed only in the workplace, without the context of family or personal history that society typically associates with mourning.

The complexity deepens when our relationship with the colleague was particularly close or, conversely, strained. We may grieve the loss of a trusted confidant, while feeling isolated from others who didn’t share that bond. Or we may feel conflicting emotions about unresolved tensions or difficult interactions, making our grief feel messy or tinged with guilt, resentment, or confusion. All of these emotional responses are valid.

Even if we didn’t personally know the colleague who passed, it’s normal to feel shaken. Death within our workplace community often touches on larger existential questions, fears, or memories of our own losses. We may find ourselves grieving not just the person, but the stability, energy, or culture that they helped shape in our work environment.

There is no "right way" to grieve. And there’s no timeline for when we should feel "back to normal," particularly when the normal we knew has been altered by someone’s absence.

Strategies for coping with the loss of a colleague

- Acknowledge and normalize your feelings: Whether you're feeling sadness, anger, guilt, confusion, or even relief, these are natural reactions. There is no hierarchy of "acceptable" emotions in grief.

- Create or participate in a shared ritual: Consider lighting a candle, sharing stories, or creating a memory board with your team. Rituals don’t have to be religious to be meaningful. They can provide structure for expressing and containing loss.

- Check in with colleagues: Grief often isolates. Making space to connect, even briefly, with coworkers to ask how they’re doing can foster a sense of support and shared humanity.

- Give yourself (and others) grace: Concentration may be harder. Energy may dip. People may react in ways you don’t expect. Extend compassion to yourself and your team as everyone processes the loss in their own way.

- Create space, if needed: Offer yourself small breaks throughout the day — whether that’s stepping outside, taking a quiet lunch, or speaking with someone you trust — to regulate and process your emotions.

- Use available support resources: Many workplaces, including ours, offer confidential counseling (FSAP) or grief support resources (Spiritual Care Services). Seeking help is not a sign of weakness. It’s a powerful step toward integrating loss in a healthy way.

- Honor their impact in your own way: Whether it’s reflecting on a lesson you learned from them or simply remembering a kind gesture, giving their presence continued meaning can be grounding.

- Respect differences in grief styles: Some colleagues may want to talk and share. Others may prefer to process internally. Avoid assumptions and allow space for everyone’s style of coping.

Grief in the workplace is real and often underestimated. By acknowledging it, supporting one another, and creating compassionate space, we can weather loss not only as individuals, but as a community.

Reference

Shoraka, H. R., Hashemi, S. A., Asghari, D., Chegeni, M., Arzamani, N., Sadidi, N., & Kaviyani, F. (2022). Mourning during COVID-19 pandemic in Bojnurd, a City in Northeast of Iran: A qualitative study. Journal of Iranian Medical Council.